January 17, 2022

Before Harvard, Kathy Delaney-Smith dominated — and revolutionized — Massachusetts high school basketball

Inside Kathy Delaney-Smith's 'Green Machine'

One night in the mid-1970s, when Erin Sugrue was in elementary school, her mother shouted for her to come downstairs and watch television. “She only did that for two reasons: One is if there was a Fred Astaire movie on and two if, I don’t know, the world was ending,” Sugrue (now Erin DiVincenzo) told The Next. “So I ran down and there was footage covering a girls high school basketball team.”

Continue reading with a subscription to The Next

Get unlimited access to women’s basketball coverage and help support our hardworking staff of writers, editors, and photographers by subscribing today.

Already a member?

Login

That team was Kathy Delaney-Smith’s Westwood High School in Massachusetts, and Sugrue was instantly drawn to what she saw. She hadn’t played organized basketball before, and she didn’t know that Delaney-Smith had built the program into a powerhouse. But, she says now, “That’s something you just want to be a part of.” And she would be: Her family ended up moving to Westwood when she was in sixth grade, and she went on to play for Delaney-Smith first in high school and then at nearby Harvard.

Delaney-Smith is best known for her four decades coaching at Harvard—and specifically for a historic NCAA Tournament game in 1998, in which her 16-seed Crimson upset top-seeded Stanford. But Delaney-Smith, who will retire after the 2021-22 season, started inspiring girls to play and excel in sports even before that, when she became a physical education teacher, the girls’ swim coach and the girls’ basketball coach at Westwood in 1971.

Getting to Westwood

“My background is kind of wacky. I wouldn’t recommend it for anyone,” Delaney-Smith told The Next.

Growing up on a lake in Newton, Massachusetts, Delaney-Smith loved swimming and ice skating, and she also starred in six-on-six basketball before Title IX. She scored over 1,000 points while playing for her mother, Peg Delaney, at Sacred Heart High School, but she pursued synchronized swimming at Bridgewater State University because there was no varsity women’s basketball team when she enrolled.

“I went to college to be a physical education and health teacher,” Delaney-Smith says. “So that was… a little bit ironic because I went to a Catholic school and I never had a PE class. So we’re not sure where that came from.”

After graduating in 1971, Delaney-Smith applied to be a physical education teacher and the swim coach at Westwood. The basketball piece came when the superintendent—who had a daughter on the team—asked Delaney-Smith in her interview whether she could also coach, and win at, basketball. “Of course I can,” she replied, even though she didn’t know much about the five-on-five game. She got the job and held all three responsibilities for most of her 11 years at Westwood, despite the overlap between the fall swim season and the winter basketball season.

Delaney-Smith excelled all three, too. In basketball, she got off to an inauspicious start, with records of 0-11 and 8-7 in her first two seasons before going 21-0 in the regular season in 1973-74.* That began a streak in which Westwood won a national-record 96 consecutive regular-season games, and she would leave Westwood in 1982 with a sterling 204-31 overall record.** Delaney-Smith’s swim teams were even better, even though she built the program from scratch: “I never lost a meet in seven years of swimming,” she says.

As a teacher, she was more skilled at some sports than others—tennis was, and still is, a particular strong suit—but she had a unique ability to reach her students. “She would just break down the barriers,” DiVincenzo says. “And she would do things like, we had to do Jane Fonda yoga … and none of the guys wanted to do Jane Fonda yoga, and she would find a way to get the guys to do Jane Fonda yoga. She just had a way about her.”

Delaney-Smith eventually gave up swimming to focus on basketball, which she decided was “way more fun” to coach. She loved the camaraderie of basketball, in contrast with how her swimmers couldn’t even hear her while competing because their heads were in the water. And she was learning more and more about basketball through books and clinics, laying the foundation for her storied career as she built it.

Learning to be successful

In Delaney-Smith’s early days at Westwood, she would often read about a drill in a book before practice and turn around and implement it. It took time for her to learn when to call timeouts. And her press offense, she says now, was “terrible.” But she has always been someone who learns from mistakes and focuses on the present, and she connected with her players as people right away.

If Delaney-Smith could go back in time, she would speed up her learning curve by networking more and asking for help. But she didn’t know who to turn to: “This is the saddest thing,” she says. “Besides my mother, I didn’t really have any [role models] because … nobody really cared about women’s sports or girls’ sports.” In addition, she felt she was “supposed to know it all” because her teams were so successful so quickly, and most opposing coaches were men who disliked her. At one coaches’ meeting, Delaney-Smith says, a male coach told her, “Look at all these coaches in this room. They hate you.”

“[It was] because we were winning,” Delaney-Smith explains. “… And I didn’t look the part. I didn’t look like I should know what I was doing. So I’m sure that was hard for people. And I didn’t have a background [in five-on-five basketball].”

Even without that background, she was soon setting the pace for her peers. She implemented an up-tempo offense that thrived in transition, fueled by a defense that pressed, trapped and blocked shots. She also changed defenses, including using a 1-3-1 zone,* to keep opponents off balance and employed a deep bench to keep her players fresh.

“We were way ahead of our time, I think, in terms of what we were doing as a girls’ basketball team,” former player Nancy (Fabiano) Woicik told The Next. “…We were pushing the ball up the floor in three or four passes, and we were the only ones doing it and doing it pretty well.” It was so revolutionary that reporter Martha Fox once wrote* that a perfectly executed fast break “was enough for Lincoln-Sudbury to call a time out in order to figure out exactly what was happening.”

“I think part of it was, not having come from a big coaching background, she didn’t know that she ‘shouldn’t’ be doing these things,” DiVincenzo says of Delaney-Smith. “… In her mind, there were no barriers.”

Perhaps another side of Delaney-Smith being relatively inexperienced was that she emphasized the basics. Francesca Busalacchi, another former player, remembers her telling the team, “Assists are just as important as points,” and urging the players to rebound better. Woicik says another common refrain was, “The plays are designed to work,” which was a reminder to focus on the details and execute offensively.

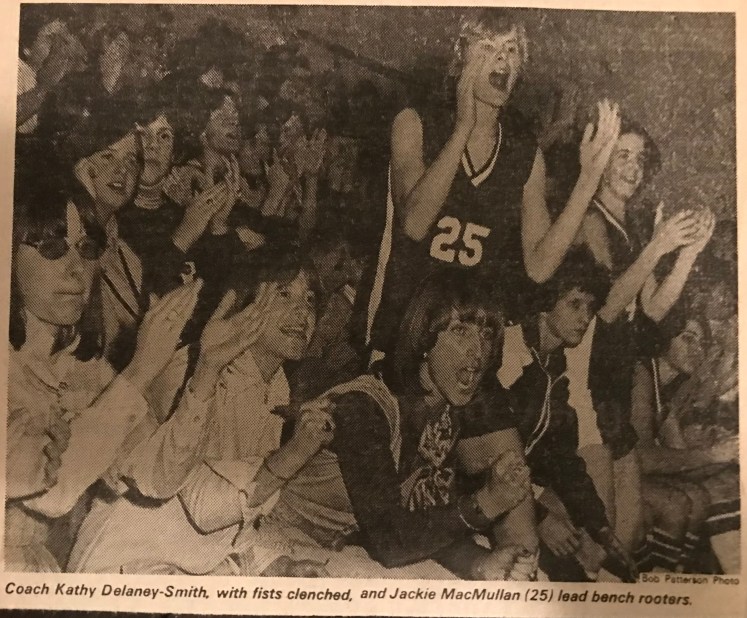

Delaney-Smith’s practices were businesslike and disciplined, according to former players, and Woicik found her “very intimidating” as a freshman. “You knew that the expectations were high,” Woicik says. Similarly, now-legendary sportswriter Jackie MacMullan wanted to play for Delaney-Smith but couldn’t muster the nerve to try out until her junior year.

The practices were so focused partly because they had to be—the team had very limited gym time, to the point that the players would warm up and stretch in the hallway to maximize their on-court time. But Delaney-Smith was also “always pushing, looking for an edge,” DiVincenzo says. Her role as a gym teacher proved useful here, as she recruited male students to be practice players for the team.

She also focused heavily on conditioning to prepare players for the up-tempo basketball she demanded. Busalacchi recalls that Delaney-Smith required the team to run 30 laps to start practice, do five wind sprints during practice, and—unusual for the time—lift weights in the offseason.

“The first practice I went to, I felt like I was at track practice,” Woicik says. “I mean, all we did was run. You didn’t see a basketball.”

Yet, amid the exacting standards, there was also a warmth to Delaney-Smith. “She was tough, but she was fair and … always praising,” Busalacchi says. “She was never critical … She was caring, but she was stern and she wanted things a certain way.”

Woicik remembers the day she got her jersey number as a freshman on the varsity team. When Delaney-Smith asked her what number she wanted, she said she didn’t have a preference. “She gave me her number, and it meant a lot to me,” Woicik says. “… I felt like at the time it was meant to be special, and I did end up being a 1,000-point scorer [like Delaney-Smith had been in six-on-six]. And that wasn’t lost on me when she gave me the number.”

‘The whole town was behind us’

When Trisha Brown, then a high school sophomore from nearby Norwood, Massachusetts, first attended a Westwood home game, she was gobsmacked. “I could not believe what I saw,” the future Harvard captain told The Next.

“One, a packed gym for a girls high school basketball game in the ‘80s was overwhelming to me and so exciting. But the Westwood High School team came out and they had tearaway sweats on. Tearaway sweats! Like, the Boston Celtics were wearing tearaway sweats. I said, ‘What is going on here?!’”

Delaney-Smith had steadily built those crowds from almost entirely players’ parents to capacity crowds that sometimes outdrew the boys’ teams. The winning and up-tempo style helped—“That’s an easy bandwagon to jump on,” she says—but she also helped it along. She organized basketball clinics, pizza parties and pregame dinners that raised awareness of and rallied the community around her team, to the point that fans would brave Northeast snowstorms to watch the local powerhouse.

“The only thing you wanted to be as a little girl growing up in Westwood is you wanted to be on the girls’ basketball team,” DiVincenzo says. “That was your goal in life and your heroes were the current team. … She built this real culture that permeated the town; the whole town was behind us.”

The result was intimidating for opposing teams from start to finish. Clad in green and white, the Westwood players took the court for warmups as Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Shining Star” blared on the record player. “We were like the Harlem Globetrotters,” DiVincenzo says.

Though Westwood was officially known as the Wolverines, the newspapers often called them the “Green Machine,” and they lived up to that billing. “The Westwood High girls’ basketball team continued to make shambles out of their opponents,” began one article during the 1976-77 season.

That season, Westwood broke the national record for consecutive regular-season wins with 73. The Boston Globe’s Neil Singelais reported that Delaney-Smith wasn’t aware of the record until a television cameraman mentioned it, and Woicik says that Delaney-Smith never discussed winning and losing with the team. But it was a big deal to everyone else: Three television crews were reportedly in attendance for the milestone win, and the radio station WHET broadcasted it.*

Local newspapers also published stories ahead of and after the historic win. The Patriot Ledger columnist Seth Livingstone wrote, “Move over John Wooden, there’s a new ‘Wizard of Westwood,’” referring to Delaney-Smith. But The Daily Transcript’s Charley Clement may have captured the excitement best:

“You can go all the way back to Oct. 1st of 1940, the day the doors opened in the first High School the Town of Westwood ever had, and you won’t find any event in the history of the School’s sports to compare with the ‘Big Game’ of last Friday. Seventy-three consecutive victories during regular season play! Absolutely unbelievable! But that’s what Coach Kathy Delaney Smith’s Varsity Basketball Team has done. Certainly it has to be the biggest thing that’s ever happened in local high school sports. And it surely put the little old town of Westwood, Massachusetts in the limelight as it set a new national record.”

Clement added that one of the officials gave his day’s pay to the mother of a Westwood player and asked her to buy ice cream for the team. “He said that it was his birthday and the girls had made it a happy one,” Clement wrote.

Even Governor Michael Dukakis took notice, inviting the team to the State House and declaring May 2 to be Westwood High School Girls Varsity Day statewide.

The winning streak finally ended in the first game of the 1978-79 season at Abington, about 20 miles southeast. Delaney-Smith recalls how posterboards about the game lined every tree from the highway exit to Abington High School and how fans were already lined up outside wearing “Beat the Streak” T-shirts when Westwood’s yellow school bus arrived. Westwood would get revenge in the postseason, but Delaney-Smith says that the loss “really hurts still. It stands out”—in part because she made the regular-season schedule.

That season, Delaney-Smith broke another streak that perhaps felt even longer, winning her first and only state title. In 1978, Westwood had lost to Drury by a single point in the final, and for several years before that, Delaney-Smith says, “we would go into tournament play and choke … So that’s bad coaching on my part.” In 1977, The Boston Globe’s Lesley Visser described Westwood as “the team of promise every year that falls in the first round.”

Part of the reason for those playoff struggles was that Westwood’s playing style—especially its press and shot-blocking—could be a double-edged sword. “In the tournament, we were just too aggressive, I think, honestly, and we got into foul trouble every time,” MacMullan told The Next. “… Our best players would be on the bench when the game was on the line.”

Woicik also says that Westwood’s dominance in the Tri-Valley League meant that the players didn’t always know how to play from behind. “I remember as a freshman [in 1973-74] losing a game and it was like, ‘Oh, my God, we’re losing. How could this happen?’ Nobody could believe it,” she says. “And I think that was part of the growing pains of the program.”

But in 1979, Westwood defeated Ipswich in overtime for the state title, with Dartmouth-bound Ann Deacon scoring 30 of Westwood’s 57 points. Along the way, the Wolverines beat Abington in the South championship by 26 points, which prompted a raucous celebration: Fans and fire trucks met the team bus at the town line, and the team rode the fire trucks back to school.

‘We’re going in’

What fans lining up to see Westwood play didn’t know was that Delaney-Smith was fighting to ensure that the school treated its girls’ and boys’ teams equally under Title IX. Her family had embraced relatively progressive gender roles, so as soon as she arrived at Westwood, the inequities jumped out at her—even when she was off the clock. She remembers attending boys’ tennis matches at Westwood and having men ask if she needed to go cook dinner for her husband.

“I’m like, ‘No, I don’t. My husband needs to cook it for me,’” she says.

As a coach, she noticed everything from her team’s lack of practice time to how it had to play sparsely attended afternoon games rather than night games to how its uniforms were field hockey skirts and turtlenecks rather than basketball shorts and jerseys.

“I remember going to Westwood High School and thinking, ‘Oh my god, this is so discriminatory … We have to make it right,’” Delaney-Smith says. “So I did. That was my personality, that you’re not going to treat girls this way.”

Delaney-Smith, then in her early twenties, filed four lawsuits against the school district. They all went to mediation instead of court and got Delaney-Smith what she wanted, including new uniforms, equal gym time and more funding.

“When I played in high school, we were wearing field hockey skirts,” MacMullan said last March on ESPN’s “Around the Horn.” “… By my senior year, I’m playing basketball—I kid you not—in tear-off sweats with my name on the back. Why? Because that’s what the boys had.”

“We had our matching sweats and we had Converse sneakers with green bottoms,” DiVincenzo says.

Delaney-Smith’s advocacy wasn’t limited to her own team, either: In 1980, she worked with the Westwood Coaches Association to raise awareness of and close pay disparities impacting coaches and staff. The school offered a 10% pay increase, but Delaney-Smith wasn’t satisfied. She told The Boston Globe, “Some of our coaches like soccer, volleyball, softball and tennis are very poorly paid … and giving them 10 percent [more] a year is not solving the problem.”

Sometimes, though, Delaney-Smith didn’t bother with a lawsuit or public lobbying—she simply refused to play second fiddle. She ended the practice of visiting junior varsity boys’ teams using the Westwood girls’ locker room—instead of other available locker rooms—by refusing to wait for them to vacate one night. Her players, returning from a road game, needed their belongings, regardless of who was in there.

Delaney-Smith had previously argued with the principal about the issue, and she warned him before the game that her players were going to enter their locker room when they got back. In response, the principal stationed a teacher named Dick Hargraves outside the locker room.

“He said, ‘Kathy, you can’t go in there. Kathy, you can’t,’” Delaney-Smith recalls. “And I go, ‘We’re going in. Dick, move aside. We’re going in.’

“And we marched right in and sure enough, there was a bunch of JV boy basketball players showering, screaming their heads off that all these girls were coming in. … I thought the girls would run around screaming, but it was the boys. It was very funny. Very, very funny. I just went into—my office was in the middle, and I just pulled all the shades down and stayed there and did my work. … [Boys’ teams] never used that locker room again.”

As she tells that story, Delaney-Smith acknowledges that she could have been fired for that decision. Instead, the ramifications of her Title IX complaints were more subtle, such as getting a worse teaching schedule and not receiving a congratulatory call from the school when she won National Coach of the Year in 1981. She also wasn’t “getting fame and fortune out of it,” MacMullan says, noting that Delaney-Smith drove a white Ford Fiesta with an orange interior.

The locker room incident was a turning point for some of the players, as Delaney-Smith had kept her Title IX fights under wraps until then. “That’s the first time I think … it registered with us,” DiVincenzo says, “like, wait a minute. When we go visit a team, when we travel, we share a locker room with the home team. When the boys play, they give the visiting team the girls’ locker room because the boys can’t be together or they’ll all fight. That was the thinking.”

In fact, most of the players The Next spoke with thought they were at Westwood when Delaney-Smith filed the lawsuits, but they weren’t entirely sure. That was by design, Delaney-Smith says: “I never want girls or women to feel like they’re second-class citizens. I felt I needed to hide it. But I would rethink that now. I think that might have been a mistake on my part to not engage them and invest them.”

A surprising exit

When Delaney-Smith interviewed at Harvard in 1982, she knew all the stereotypes—and she initially wanted no part of that. She was happy at Westwood, thought there was more work to do on Title IX, and had no interest in college coaching.

“I just did it out of a professional obligation and nothing more,” she says. “And [I] fell in love with this place on that one day … Harvard wasn’t what I thought it was.”

Delaney-Smith was the only high school coach that Harvard considered, according to The Boston Globe, and her hiring rocked the town of Westwood. “I remember just being a little shocked that she made that huge jump,” MacMullan says. “… It was pretty stunning when she left. I think everybody just thought, well, she’ll be here forever.”

In some ways, Delaney-Smith repeated her Westwood experience in her first few seasons in Cambridge. She felt “like a fish out of water” because she had never been an assistant at the college level, and she had to learn how to recruit for the first time. She won just 24% of her games in her first three seasons (18-57) before winning the Ivy League title in 1985-86—the first in program history.

Despite being just 20 miles away, Delaney-Smith rarely returned to Westwood, both because she wanted to give her successor space to mold the program and because many people were upset that she had left. When she did stop by to recruit, she had an intimidating presence—and not just because a banner on the gym wall bore her name.

“She had—you know those long swim team jackets that say Harvard on the back, like they’re giant, floor-length? It was like Darth Vader. She would walk in and we were like, ‘Ahhh!’” DiVincenzo says.

Delaney-Smith had immediate success on the recruiting trail, signing Brown and DiVincenzo as part of an eight-player freshman class that enrolled in 1983. DiVincenzo is the only player to have played for Delaney-Smith at both places, and she was crucial to Delaney-Smith’s transition.

“She only played basketball two years [at Harvard] … but she was a great program player [with] her energy, her work ethic,” Delaney-Smith says. “I knew I needed someone to teach my players how to work hard and how to be invested and have energy and body language and all that stuff. … The best thing I ever did was recruit Erin.”

Beyond the wins, Delaney-Smith’s love and lessons stand out

Several years ago, an event honoring Delaney-Smith attracted many former Westwood and Harvard players—and illustrated her enduring impact.

“As the night went on, these two camps kind of formed, the Harvard alumni and the Westwood alumni, basically [over] who knows and loves Kathy best,” says DiVincenzo. “… Everybody was really protective and had this ownership … I was like, ‘Okay, ladies, settle down.’”

They all felt that pull—some almost 50 years later—because Delaney-Smith has built her career on relationships. “She knew our families. She knew my brothers, my parents … We knew her family, we knew her siblings, we knew her mother,” Woicik says. In fact, Peg Delaney could sometimes be found knitting in Delaney-Smith’s office, eager to talk about basketball and get to know the players.

Delaney-Smith occasionally hosted the Westwood players at her house on weekends, Busalacchi and Woicik recalled, just to hang out and talk about basketball and life. It was low-key but “special,” Woicik says. “I don’t know a player that would ever miss that opportunity … to spend that time with her.”

“We were like one big happy family with her and with our families,” Busalacchi says. “It brought a lot of teammates’ families together. And we all had this one really cool mission … to win games for Kathy Delaney-Smith. She made it fun and she made it exciting.”

At school, Delaney-Smith’s office door was always open to students, regardless of whether they played for her. Busalacchi confided in Delaney-Smith about being raised by a single parent after her father died, and MacMullan shared her dream of becoming a sportswriter—then a nearly exclusively male profession.

“She was one of the first people besides my parents that ever said to me, ‘Well, you can be anything you want,’” MacMullan says. “… That’s a pretty empowering thing when someone that you look up to says that to you and believes in you like that.”

For Woicik, her relationship with Delaney-Smith was especially meaningful because she was otherwise constantly grouped with and recognized alongside her triplet sisters. “I think [playing for Kathy was] the first time I really felt that I was being seen as an individual,” she says.

Along with her care for the players, the life lessons that Delaney-Smith taught left a lasting impression. She did that indirectly, by giving girls opportunities to learn about life through sports, but also quite directly. DiVincenzo vividly remembers returning to practice after Christmas one year and Delaney-Smith calling out the players for not wishing her a merry Christmas before the holiday break.

“She was like, ‘That’s not okay.’ And it was the first time someone had said that … basically, you’re spoiled. You have to recognize that there’s a world out there and you have to be sensitive to what other people need. And no one had really done that for us.”

Delaney-Smith also helped several players earn college scholarships at a time when top girls’ players drew much less attention than boys. Her alumnae played at schools including Harvard, Dartmouth, Providence, New Hampshire, Fairfield, Maine and Holy Cross. Many of them also eventually coached basketball, paying forward what Delaney-Smith had taught them.

“I don’t know the exact number of wins and losses that we had,” Woicik says. “But I do remember playing for somebody who was very caring about me not only as a player, but as a person.”

Delaney-Smith’s Westwood career still resonates

Westwood High School has remained a strong program since Delaney-Smith left, dominating the Tri-Valley League throughout the 1980s and winning back-to-back state titles in 2001 and 2002. The only person to question Delaney-Smith’s role in getting it started seems to be the coach herself.

“The woman that came in after me did a great job and won a title … so it wasn’t me,” Delaney-Smith says. Questioned further, she concedes, “It might’ve been a little bit me.”

“The train kept chugging along, but no one’s going to argue who set the tone for it and who set the foundation,” MacMullan says. “It was her.”

Although Delaney-Smith was at Westwood for only a fraction of the time she has patrolled the Harvard bench, the former is worth revisiting and celebrating as Delaney-Smith’s final game approaches. Westwood High School is where Delaney-Smith discovered her love of coaching and showed how far a nurturing coach with high standards and a voracious appetite for learning can take a team. It’s where she demonstrated how, with a bit of investment and a lot of belief and hard work, a powerhouse girls’ program could be built.

“I guess I will always keep trying to figure out what it was that I was doing so right,” Delaney-Smith says. “It probably didn’t feel like I was … [I felt like,] I just work hard, and everybody works hard. … But it’s a style of leadership and management that I was using well before anybody … It works, I think, with everyone, but it clearly worked with young girls and women.”

For the Wizard of Westwood and those who played for her, the results were simply magical.

*According to an undated newspaper clipping provided by Francesca Busalacchi.

**There is some debate over this number, with various reports putting the streak between 94 and 99 games. The Next uses 96 games because that is the number cited in Delaney-Smith’s official bio on the Harvard website (and by other sources).

Written by Jenn Hatfield

Jenn Hatfield is The Next's managing editor, Washington Mystics beat reporter and Ivy League beat reporter. She has been a contributor to The Next since December 2018. Her work has also appeared at FiveThirtyEight, Her Hoop Stats, FanSided, Power Plays, The Equalizer and Princeton Alumni Weekly.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Women’s basketball fanatic. they did not have organized sports for girls growing up where i lived. Started following Tara Vanderveer in the 70’s and then Discovered Pat Summitt! Thank you for this exceptional story. Who knew Jackie could ball .. GoVols

Such a tremendous story of an outstanding woman, coach and role model. I grew up going to her overnight basketball camps in NH and then in Cambridge… no one knew how to motivate a crowd like Kathy. And you always wanted to be on your “A-game” in her presence. Sad to hear she’s retiring – I take my girls to her college games now and wish she’d stick around so we can all enjoy her fire, spirit and legacy.